Three years ago, when I made my first photo tour through the magnificent landscapes of Iceland, I fondly recall an interesting dinner discussion with my fellow photographers. We had just returned to our guest house from a memorable photo shoot. As we shared good wine, food, and laughs, the discussion pleasantly turned to photography. After the seemingly prosaic and obligatory discussion of camera gear, we got around to more interesting topics such as light, travel destinations, and our individual exploits. One pleasant, wise, and well-traveled gentleman from Holland made an interesting comment that has resonated with me ever since. With a blend of delight and amusement, he said, and I paraphrase him:

“It’s amazing how photographers can travel to the same place at the same time and come away with completely different photographs.”

He chuckled as he said that, and his comment drew smiles and nods from the group. Interestingly, there was a pause with confounded looks, and the discussion quickly turned to other topics in photography. In retrospect, what the gentleman from Holland remarked was not only interesting but the truth – a truth whose basis is the epitome of the visualization process. That is to say, unique artistic constructs are molded by different life experiences and likely influenced by the predominant emotion at the time of making the photograph. The same scene, yet different visions, different interpretations, and thus, different photographs. Over the years since that dinner discussion, I have pondered a related question, “How can the same photographer travel to a similar subject and come away with the same photographs?” Not that there is anything inherently wrong with that, yet for me it has been a challenge to photograph the same subject and come away with distinct and more interesting images. For me, the answer to that question became manifest: I had to change my vision.

The Algodones Dunes

I have hiked and photographed sand dunes in Southern California multiple times, stretching from the Kelso Dunes in the Mojave National Preserve to the Mesquite Flat Dunes in Death Valley National Park. Yet, there is a stretch of dunes that I had not yet explored, the Algodones Dunes, widely known for all terrain vehicle recreation. Since I was in the mood for exploring a new place, exploring the intersection of light and land, and since these dunes are a short 2.5-3 hour drive from my home base in San Diego, CA, I decided to take a chance. Three months ago, I made a brief 2-day road trip to these dunes to make photographs of the terrain in a way that I had not yet done with enough emotion and creativity. I embarked with a clearly defined goal: to explore light, shadows, and contrast to create a new rendition of a familiar subject.

The Algodones Dunes, also known as the Imperial Sand Dunes, are a vast stretch of dunes in the Sonoran Desert deep in Southeast California, near the California-Arizona and US-Mexico borders. It encompasses the North Algodones Dunes Wilderness, which is a protected natural habitat that is off-limits to recreational vehicles, and the Imperial Sand Dunes Recreational Area. It is the latter that boasts the more impressive stretch of sand dunes. Although I had understood the landscape in the region that I would be entering (Osborne Overlook off Hwy 78) at this particular time of the year (winter-early spring), would undoubtedly be marred with tire tracks from all terrain vehicles, I was not overly concerned about it. My interest was not in photographing a pristine landscape, but more in exploring light, shadows, textures, and patterns. As I surveyed the scene, I immediately became interested in the abstracts that I could potentially make (with or without the tire tracks). Given my artistic imperative at the time, I felt reasonably good about the prospects for making interesting images. The only question in my mind was: at the decisive moment of opening the shutter, what specific subjects would materialize?

Kelso Dunes

Mamiya 7II, 43mm f/4.5, Fujichrome Velvia 50

Mesquite Flat Dunes

Nikon D800, 100mm f/2.8 E Series

Whenever I embark on a photo shoot, in particular landscapes, I do so possessing one of two mind sets. One, I have a very specific subject of interest, most likely a subject that I have scouted and all that I need is for Mother Nature to provide the light to consummate the visualization process. Alternatively, I set out for a specific quality of light for which I am confident will materialize, yet I do not have a well-defined subject in mind. Then based on the light, I will seek out a subject based on my mood and emotion at the time. For me, both approaches are not mutually exclusive; but whatever photograph I end up making, one of these approaches will have been paramount. For this photo shoot, I took the latter approach. Based on the weather reports, I knew with a high degree of certainty that I would have the desired light in abundance (unidirectional and high contrast under clear skies), but my specific subject would need to materialize at the moment, as if in an epiphany, or serendipitously. Previously, I have written about the former approach taken to the nth degree.

To create the photographs below, I used one of my favorites tools – panchromatic black and while film. With the exception of one photograph, I used a 35mm camera, which is one of my preferred tools under conditions where light is changing rapidly, where I desire to change locations and compositions quickly, and where I desire to take multiple exposures in a short amount of time. It goes without saying that for the black and white landscape photographer, it is all about *contrast*, pure and simple. To yield the contrast that I visualized, I used a classic tool in black and white photography, the deep red filter. For more background on the red filter and the technical rationale, you can read here and here. With the exception of one photograph below, I used an exposure strategy that would yield strong highlights balanced with deep shadows to create contrast and depth and impart a sense of intrigue and mystery to the scene. For all of these photographs, I used a long lens to frame the perspective.

It would be worthwhile to pause briefly to explain the relationship between the directionality of light and texture, although a dedicated article would surely be merited down the road. In general, whether the artist is a photographer, a painter, or a sketch artist, textures are best revealed by two directions of incident light: lighting from the side and back lighting. For the landscape photographer, light that sweeps across the landscape from the side has been a cherished tool for revealing textures and lending shape and dimensionality to the scene, although backlighting can accomplish the same feat. A good on-line resource that nicely illustrates the relationships between the directionality of light and texture can be found here with an excellent book written by the same author that I highly recommend.

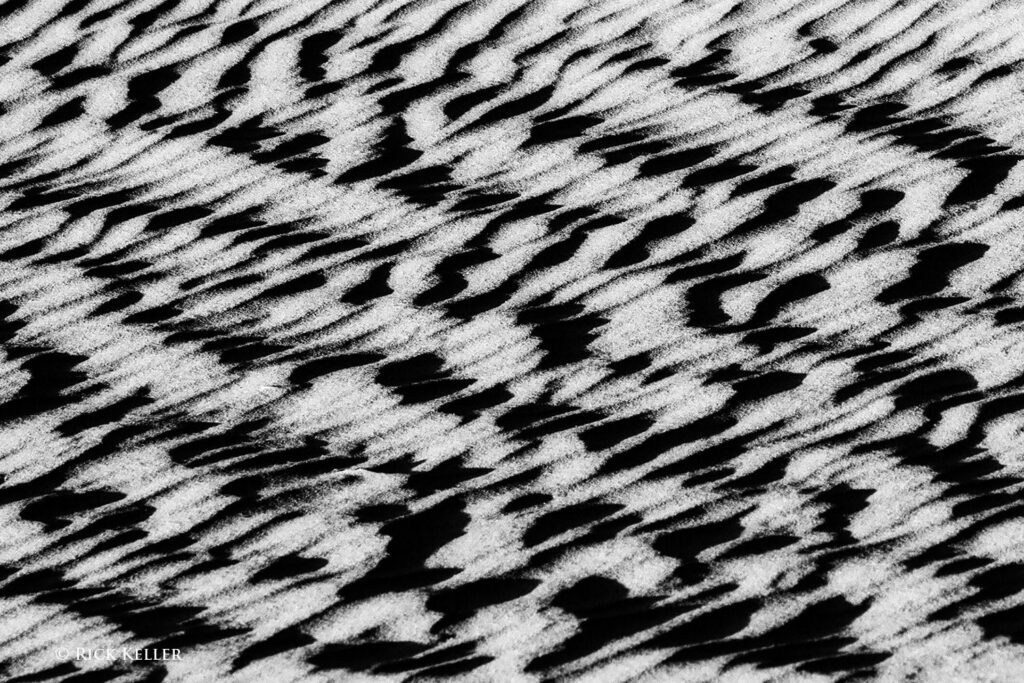

For this first photograph at mid-morning, I visualized a blend of coarse and smooth textures. As the sun was rising higher, the shapes and deep shadows gradually materialized. In the midst of the depressions and deep shadows in the dunes, my mind saw the nose of a human face in the bottom of the frame. It was uncanny. With this emotion gripping my consciousness at that moment in time, I felt compelled to open the shutter.

Nikon F6, Nikkor 70-200mm f/4 G ED VR, Adox CMS 20 II

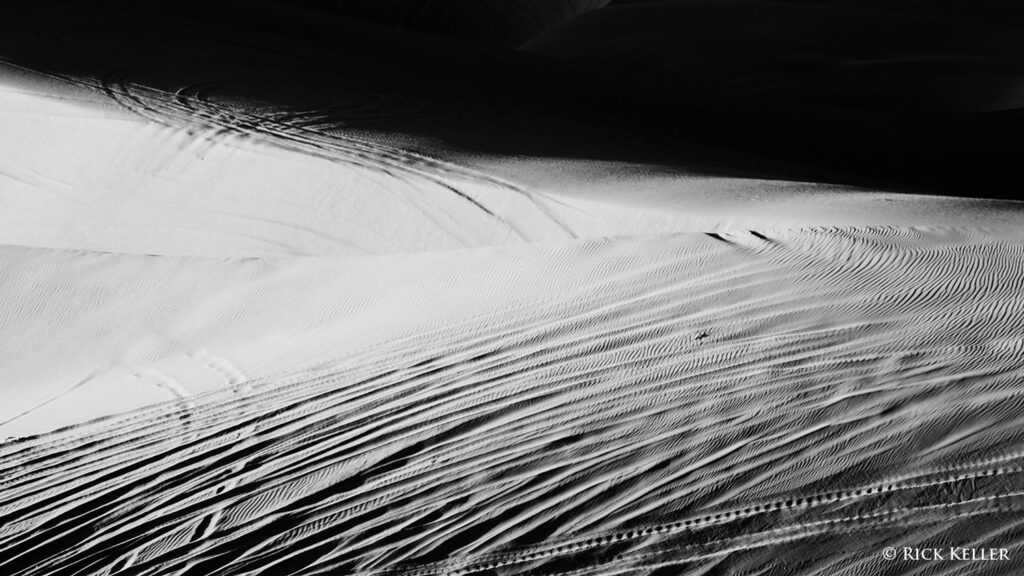

For this next photograph (my first exposure of the morning), the sun was starting to clear the Chocolate Mountains and bathe the landscape. As I previously discussed about this scene here, I was feeling an emotion of scarred beauty, an emotion of mystery, and that of an untold story. I again “saw” and “felt” the contours of a human face, and as the contrast was building up, I was “feeling it”. The lighting, which was highly unidirectional and contrasty, was sweeping across the subject at a nearly 90 degree angle, which casted long and deep shadows. At that decisive moment, the light, shadows, and emotion were aligned, and I again felt compelled to open the shutter. In retrospect, the wait to see this particular negative on the light table was immensely gratifying. It was almost like re-living a love affair with light and then re-uniting with your love days later . . . Sighh . . . It was pretty awesome. 🙂

Nikon F6, Nikkor 70-200mm f/4 G ED VR, Adox CMS 20 II

As the sun was rising higher, I was still inspired with a human emotion embedded within the landscape, and I just rolled with it . . . As I surveyed the scene looking for my next subject, my eyes caught another set of depressions, curves, and contours. At that moment, my mind interpreted the contours of a human torso. In the midst of the light display, I saw an abdomen, a navel, a waistline, and hips . . . She was beautiful! It was another uncanny sight, and it felt right for making another exposure. The quality and directionality of the light – sweeping from above and to the side – was conducive to creating shape and 3-dimensionality and revealing fine textures on the sand. Although I was shooting directly into the path of the sun, the reduced contrast from flare did not deter me, as I knew what I was seeing in my mind could not be witnessed from another direction of light.

Nikon F6, Nikkor 70-200mm f/4 G ED VR, Adox CMS 20 II

Since I’ve been photographing sand dunes (and beaches) over the last past four years, I have found that potentially interesting compositions may actually lie not far ahead but literally underneath your feet. Again, if the incident sunlight is from the side or in front of you, with careful study through a composing card, the potential for the mind to see patterns and abstracts can be alluring, as the following two photographs illustrate.

Nikon F6, Nikkor 70-200mm f/4 G ED VR, Adox CMS 20 II

Nikon F6, Nikkor 70-200mm f/4 G ED VR, Adox CMS 20 II

In contrast to proximity and abstracts, again with careful study of the landscape and the light through the composing card and a long lens, even a distant scene may declare itself to be a delightful interplay of light, shadows and texture conveyed with a sense of minimalism.

Nikon F6, Nikkor 70-200mm f/4 G ED VR, Adox CMS 20 II

What I enjoy about long deep shadows in a landscape is that they have the potential to confer different emotions and physical interpretations of a scene. From an emotional perspective, as I have mentioned deep shadows can provoke a mood of intrigue, mystery, drama, and a sense of abstraction. From a physical perspective, they can lend shape, depth, and 3-dimensionality to the scene. Consider the next two photographs.

Nikon F6, Nikkor 70-200mm f/4 G ED VR, Adox CMS II

Nikon F6, Nikkor 70-200mm f/4 G ED VR, Kodak T-Max 100

The first illustrates how the deep shadows lend a sense of depth and an element of mystery to the scene, whereas the second photograph – taken later in the morning when the sun was higher in the sky – reveals greatly diminished shadows, which unfortunately impart a bland mood as well as a flattened perception of depth. The same subject . . . The same perspective . . . Different lighting . . . Two starkly different photographs, emotionally and physically.

Although a view camera is not my first tool of choice under rapidly changing lighting, I brought my 4×5 with me because I was both stubborn and felt that I would easily find an appropriate subject for a couple of exposures. For this next photo, which was the last photo I made on my trip, I had scouted the dunes north of Hwy 87 (the area that is restricted from all terrain vehicles) and found a stretch of low-lying dunes where the light from the setting sun would strike it at a low angle from the side and potentially reveal more interesting textures and deep shadows. At sunset, the light was creating lovely tonality across the sand and becoming more enticing as the minutes passed. This was another shot where “I was feeling it”. After honing my composition with my card and adjusting it on the ground glass, the sharp curved line conveyed an emotion of two separate worlds . . .

Ikeda Anba 4×5, Nikkor-M 300mm f/9, Ilford Delta 100

Since my goal with this particular photograph was to capture a broad range of tones and preserve shadow detail, I deliberately did not use a contrast filter (e.g., red, orange, yellow, or green), since such a filter would have blocked blue light and reduced shadow detail. I did, however, use a UV filter to block UV light from exposing the film. Briefly, from a technical standpoint, I spot metered the shadows in the middle right of the frame to preserve those on Zone II, then extended the development of the film by N+1 to expand the high values, and thus the overall contrast range. This was my personal favorite exposure of the trip: a pleasant tonal range, replete with textures, and still conveyed with a sense of mystery yet with less drama than in the previous images.

Conclusions

In a recent conversation with Howard Bond, with whom I have had the privilege to periodically share thoughts on art, photography, and history, Mr. Bond remarked, “It’s wonderful to see that there is a lot going on in your head when you are photographing.” That comment resonates with me as much as the comment from the gentleman from Holland, for similar reasons. The process of modifying a vision, changing an established way of interpreting a scene, or thinking outside of the box is not an easy one for a photographer and artist. This is the most challenging aspect in the creative process. For this photo shoot, following weeks of contemplation and refining a specific goal and vision coupled with the appropriate light, I was able to create a set of photographs that were distinct in meaning and emotion from my earlier photographs of a similar subject. For the contemplative photographer, the visualization process starts with feeling it and believing in it. The light and the skill of the photographer will take care of the rest.